Gaming out the battle plan

In a conference call in the late fall of 2022, after Kyiv had won back territory in the north and south, Austin spoke with Gen. Valery Zaluzhny, Ukraine’s top military commander, and asked him what he would need for a spring offensive. Zaluzhny responded that he required 1,000 armored vehicles and nine new brigades, trained in Germany and ready for battle.

“I took a big gulp,” Austin said later, according to an official with knowledge of the call. “That’s near-impossible,” he told colleagues.

In the first months of 2023, military officials from Britain, Ukraine and the United States concluded a series of war games at a U.S. Army base in Wiesbaden, Germany, where Ukrainian officers were embedded with a newly established command responsible for supporting Kyiv’s fight.

The sequence of eight high-level tabletop exercises formed the backbone for the U.S.-enabled effort to hone a viable, detailed campaign plan, and to determine what Western nations would need to provide to give it the means to succeed.

“We brought all the allies and partners together and really squeezed them hard to get additional mechanized vehicles,” a senior U.S. defense official said.

During the simulations, each of which lasted several days, participants were designated to play the part either of Russian forces — whose capabilities and behavior were informed by Ukrainian and allied intelligence — or Ukrainian troops and commanders, whose performance was bound by the reality that they would be facing serious constraints in manpower and ammunition.

Russia held these Ukrainian teens captive. Their testimonies could be used against Putin.

The planners ran the exercises using specialized war-gaming software and Excel spreadsheets — and, sometimes, simply by moving pieces around on a map. The simulations included smaller component exercises that each focused on a particular element of the fight — offensive operations or logistics. The conclusions were then fed back into the evolving campaign plan.

Top officials including Gen. Mark A. Milley, then chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Col. Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, commander of Ukrainian ground forces, attended several of the simulations and were briefed on the results.

During one visit to Wiesbaden, Milley spoke with Ukrainian special operations troops — who were working with American Green Berets — in the hope of inspiring them ahead of operations in enemy-controlled areas.

“There should be no Russian who goes to sleep without wondering if they’re going to get their throat slit in the middle of the night,” Milley said, according to an official with knowledge of the event. “You gotta get back there, and create a campaign behind the lines.”

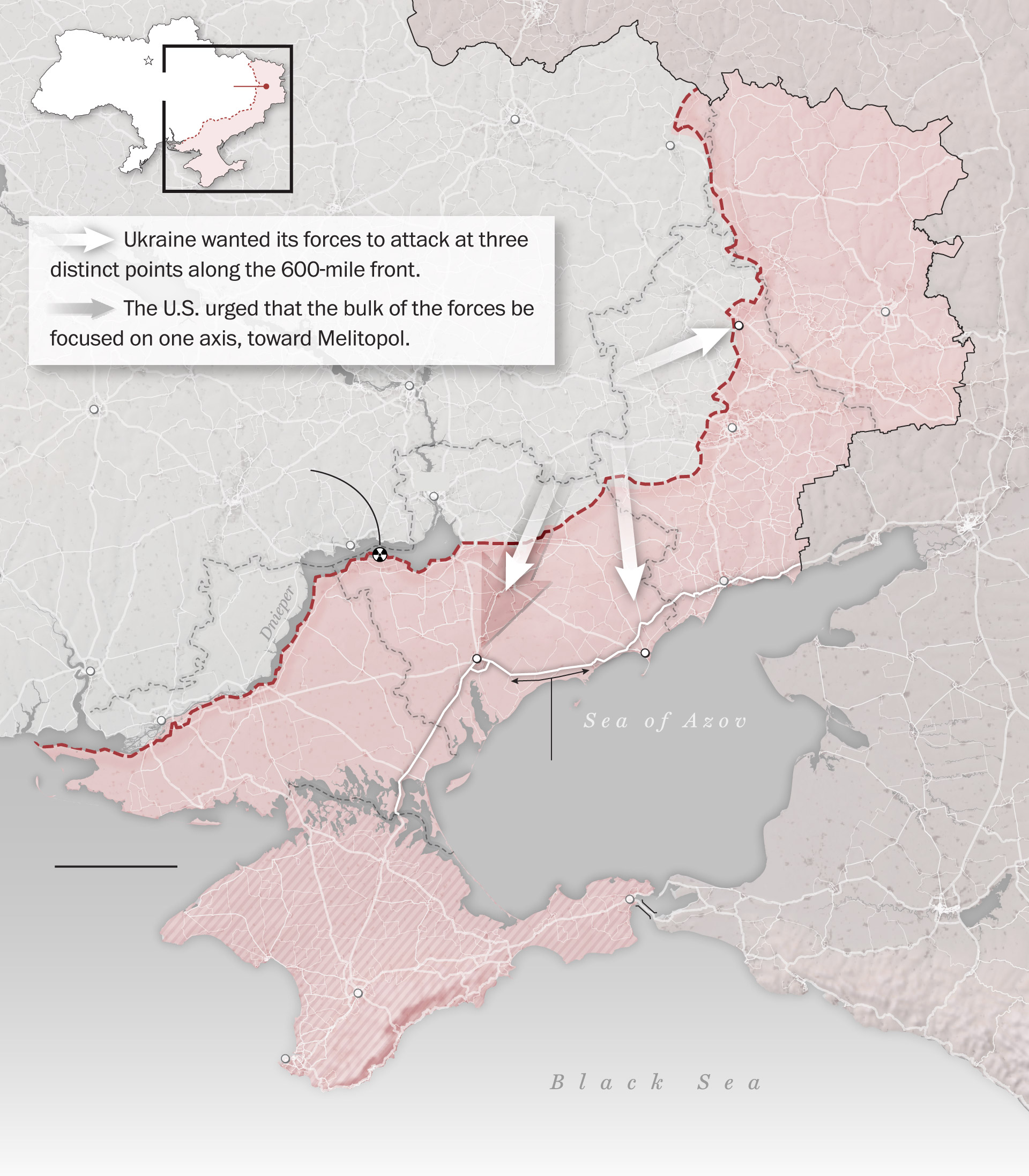

Ukrainian officials hoped the offensive could re-create the success of the fall of 2022, when they recovered parts of the Kharkiv region in the northeast and the city of Kherson in the south in a campaign that surprised even Ukraine’s biggest backers. Again, their focus would be in more than one place.

But Western officials said the war games affirmed their assessment that Ukraine would be best served by concentrating its forces on a single strategic objective — a massed attack through Russian-held areas to the Sea of Azov, severing the Kremlin’s land route from Russia to Crimea, a critical supply line.

The rehearsals gave the United States the opportunity to say at several points to the Ukrainians, “I know you really, really, really want to do this, but it’s not going to work,” one former U.S. official said.

At the end of the day, though, it would be Zelensky, Zaluzhny and other Ukrainian leaders who would make the decision, the former official noted.

Officials tried to assign probabilities to different scenarios, including a Russian capitulation — deemed a “really low likelihood” — or a major Ukrainian setback that would create an opening for a major Russian counterattack — also a slim probability.

“Then what you’ve got is the reality in the middle, with degrees of success,” a British official said.

The most optimistic scenario for cutting the land bridge was 60 to 90 days. The exercises also predicted a difficult and bloody fight, with losses of soldiers and equipment as high as 30 to 40 percent, according to U.S. officials.

American military officers had seen casualties come in far lower than estimated in the major battles of Iraq and Afghanistan. They considered the estimates a starting point for planning medical care and battlefield evacuation so that losses never reached the projected levels.

The numbers “can be sobering,” the senior U.S. defense official said. “But they never are as high as predicted, because we know we have to do things to make sure we don’t.”

U.S. officials also believed that more Ukrainian troops would ultimately be killed if Kyiv failed to mount a decisive assault and the conflict became a drawn-out war of attrition.

But they acknowledged the delicacy of suggesting a strategy that would entail significant losses, no matter the final figure.

“It was easy for us to tell them in a tabletop exercise, ‘Okay, you’ve just got to focus on one place and push really hard,’” a senior U.S. official said. “They were going to lose a lot of people and they were going to lose a lot of the equipment.”

Those choices, the senior official said, become “much harder on the battlefield.”

On that, a senior Ukrainian military official agreed. War-gaming “doesn’t work,” the official said in retrospect, in part because of the new technology that was transforming the battlefield. Ukrainian soldiers were fighting a war unlike anything NATO forces had experienced: a large conventional conflict, with World World I-style trenches overlaid by omnipresent drones and other futuristic tools — and without the air superiority the U.S. military has had in every modern conflict it has fought.

“All these methods … you can take them neatly and throw them away, you know?” the senior Ukrainian said of the war-game scenarios. “And throw them away because it doesn’t work like that now.”

Disagreements about deployments

The Americans had long questioned the wisdom of Kyiv’s decision to keep forces around the besieged eastern city of Bakhmut.

Ukrainians saw it differently. “Bakhmut holds” had become shorthand for pride in their troops’ fierce resistance against a bigger enemy. For months, Russian and Ukrainian artillery had pulverized the city. Soldiers killed and wounded one another by the thousands to make gains measured sometimes by city blocks.

The city finally fell to Russia in May.

Zelensky, backed by his top commander, stood firm about the need to retain a major presence around Bakhmut and strike Russian forces there as part of the counteroffensive. To that end, Zaluzhny maintained more forces near Bakhmut than he did in the south, including the country’s most experienced units, U.S. officials observed with frustration.

Ukrainian officials argued that they needed to sustain a robust fight in the Bakhmut area because otherwise Russia would try to reoccupy parts of the Kharkiv region and advance in Donetsk — a key objective for Putin, who wants to seize that whole region.

“We told [the Americans], ‘If you assumed the seats of our generals, you’d see that if we don’t make Bakhmut a point of contention, [the Russians] would,’” one senior Ukrainian official said. “We can’t let that happen.”

In addition, Zaluzhny envisioned making the formidable length of the 600-mile front a problem for Russia, according to the senior British official. The Ukrainian general wanted to stretch Russia’s much larger occupying force — unfamiliar with the terrain and already facing challenges with morale and logistics — to dilute its fighting power.

Western officials saw problems with that approach, which would also diminish the firepower of Ukraine’s military at any single point of attack. Western military doctrine dictated a concentrated push toward a single objective.

The Americans yielded, however.

“They know the terrain. They know the Russians,” said a senior U.S. official. “It’s not our war. And we had to kind of sit back into that.”